Theoretics

Architectural Composition At The École Des Beaux-Arts In Paris

“École des Beaux-Arts of Paris taught architecture from 1819 to 1968” (DREXLER, 1984, p. 61).

Academies, intended for all branches of art, proliferated from the absolutism of King Louis XIV, as a way to ensure royal power. But with the transformations of society in France and mainly from the French Revolution, 1789, they were extinguished and seen as a symbol of the previous political structure.

Despite the closure of the academies, the schools of some of them were maintained, due to their recognized usefulness to society. The transformation of two of these schools, the Academie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture and the Academie Royale d’Architecture, between 1793 and 1819, resulted in the École des Beaux-Arts of Paris. Some of its teaching structure survived from the Ancien Régime.

According to ZANTEN (In DREXLER, 1984), French academic architecture went through three distinct phases. The first was a formative period, between the founding of the Académie Royale d’Architecture (1671) and the French Revolution (1789). In this period, the institutions themselves organized their statutes, normally with little efficiency. The propagated theories were formulated in academic discussions and in lessons given in architects' ateliers. The second phase extended from the establishment of academic institutions until the 1860s, and was the most significant period of the system, in which great names from all factions of French architecture taught, such as Henri Labrouste, Charles Garnier, among others. The third phase began in the 1870s as a result of the previous period. This phase marked the internationalization of the beaux-arts system, with the formation of several foreign students who would carry out variations of it in their places of origin. At the same time, the decline of the school seems to have begun, as it became exclusive and ossified.

Throughout the 19th century, the main manifestations of the Beaux-Arts tradition were the works that won the Grand Prix, an award in the annual student competitions that even granted trips to Italy to study classical monuments.

Composition was the system term for the essential act of architectural design. “What composition meant was not just the design of ornaments or facades, but of entire buildings, conceived as three-dimensional entities and seen together in plan, section and elevation.” (DREXLER, 1984, p. 112). This term was constituted as a distinction between two more specific ones that denoted “planning”: distribution, which referred to the convenience and functionality of the parts, and disposition, which referred to the proper ordering of these parts. At the same time that composition was widely used, another term gained importance at the École: parti. While composition purely designated realization and union, parti referred to inspirations and choices. Before this term, it used to be said (especially Quatermère de Quincy) conception, which had a denotation linked to “a first idea”, an “artistic creation”.

École des Beaux-Arts came to believe that it had created an infallible design method (more than that, a technique), valid regardless of the designers' individual choices. This led to the so-called “battle of styles”, in which the differential of the architecture carried out was the stylistic garments. This superficiality ended up leading to great criticism, especially during the Modern Movement, in the 1920s, which sought to oppose a commitment to architectural “substance”.

The basic idea of architectural composition was to conform the interior and exterior of buildings, that is, that the exterior masses indicate and harmonize with the interior spaces:

“The way in which the student arranged these spaces and volumes was to group them along axes, symmetrically and pyramidally. The basic solution for the composition of a monumental construction in an unobstructed place (the type of construction and the place usually specified in the school) was discovered almost immediately: two axes [...] intersecting at right angles in the largest central space, the whole compressed inside a circumscribed rectangle.” (ZANTEN In DREXLER, 1984, p. 118).

Right from the first application of this solution, a problem arose that survived until the 20th century: how to establish a direction in the drawing, a front and a background. The most frequent answer was to treat the cour d'honneur (court of honour) as the open center of an axial cross plan contained in two concentric rectangles, with the front side completely removed, and each of the three remaining sides facing the courtyard receiving a central feature (figure 1).

ZANTEN (In DREXLER,1984) also observes:

“The tension seen in Grand Prix designs between biaxially symmetrical planes and directional arrangements is characteristic of a basic conflict in Beaux-Arts composition: that between the purity of geometric pattern and the circumstantial distortions required for the fulfillment of the given function and for the expression of that function.” (p. 124).

The need for the Beaux-Arts method of composition to deal with technical and functional issues without losing coherence led to the emergence of a new design technique, which brought together specific small techniques already developed at the end of the 18th century. This technique appeared in Charles Percier's Grand Prix winning design of 1786, a "Building to Gather the Academies". It consisted of “reducing almost all spaces to rectangles adhering to a continuous modular grid greatly increasing the ease with which they could be combined and manipulated.” (ZANTEN In DREXLER, 1984, p. 129). It was something totally new in the Renaissance tradition of the École, which brought great contributions. The “rectangle within a rectangle” figure and the overlapping of external rectangles, as the main results of this technique became known, began to allow the separation of functional spaces and communications:

“This introduced a web of multiple readings over the surface of the plan and created a system of secondary axes along the junction lines of the main spaces [...]. These secondary axes also became lines of movement and vision [...].” (ZANTEN In DREXLER, 1984, p. 129).

After the French Revolution, Grand Prix-winning designs exhibited a greater simplicity and urban awareness, provided by the larger and more complex themes given. The École des Beaux-Arts as a scholastic organization slowly matured during the years 1792 to 1840, and in parallel the student exercises matured as well. During the 1820s and 1830s new ideas appeared in France that could not fit into the system. They began with the works of the then students Duban and Labrouste, in 1828 and 1829:

“These projects were intended to summarize everything that the best students had learned during a decade and a half at the Ecole, horrifying the academy. The ideas these designs embodied were banned from Grand Prix competition until the end of the century [...]” (ZANTEN In DREXLER, 1984, p. 138).

The famous architect and theorist Etinne-Louis Boulée stands out, who for the first time denied the importance of columns and orders in architecture; an importance that had always been one of the bases of the classical tradition. He suggested that the building masses themselves, experienced in light and shadow, were the elements of architecture, to be ordered symmetrically in a precise pattern. More than that, Boulée suggested four architectural modes based on the four seasons. For example, summer effects were characterized by intense light, glare, and strong colors, while winter effects were characterized by dark, dreary light and hard, angular shapes. Thus, each mode would be suitable for certain types of buildings.

Also noteworthy is another architect and theorist, Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, who taught architecture at the Ecole Polytechnique:

“His method was to 'decompose' and 'analyze' historical and traditional architecture as a series of elements – loggias, balconies, vestibules, rooms, stairs, galleries, courtyards – physical entities, without sensitive or symbolic implications. This he rearranged according to a modular grid and an elementary vocabulary of columns, walls, flat roofs and vaults, and then synthesized along grid patterns to generate ensembles.” (ZANTEN In DREXLER, 1984, p. 193).

As the Grand Prix competitions of the 1840s continued along the same lines and designs evinced less and less imagination and conviction, a change began to take place. Since the previous decade, notably three architects, Félix Duban, Henri Labrouste and Léon Vaudoyer, taught in their ateliers ideas and points of view that contrasted with the current Beaux-Arts system. Over time, these ideas propagated and reached projects competing for the Grand Prix. The Ecole then began to accept them and a winning project at that time, the Bourse (stock exchange) by Gabriel Davioud, already showed itself to be outside the traditional canons, breaking with the prevailing geometric paradigm (the network of rectangles), emphasizing the structural system and presenting a loggia as a detached and independent element in the volumetric composition.

Henri Labrouste became famous throughout the 19th century for creating a kind of “Neo-Greek” style, which began at the Sainte-Geneviève Library (Paris, 1849), with very sober ornamentation and a large number of idyllic and mythological paintings. This style was followed by other contemporary architects, such as Gabriel-Auguste Ancelet in his Monument to Napoleon on the Island of Saint Helena (1849).

Another contribution to breaking the old Beaux-Arts tradition was the work of the architect Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, who sought to create architectural spaces characteristic of the 19th century through the combination of masonry and iron (figure 2). His most famous result was a vaulted hall, dating from 1864, whose vaulted ceiling was half of a regular polyhedron. Viollet-le-Duc also drew comparisons between architecture and geology, which he set out to study.

At the same time, works by Grand Prix winners, carried out on their trips to Italy, also began to look different; mainly due to the focus on decorative systems other than the classic Greco-Roman one. Of course, the Ecole protested. The Beaux-Arts system was based on the belief that the architecture of classical antiquity represented an eternal, unchanging ideal of beauty and order.

This was the first symptom of the arrival of Romanticism in architecture, around the 1830s. Imbued with this spirit, a group of architects led by Léon Vaudoyer began to propagate the idea of the transience of the history of architecture, through which each society, each place and each historical moment, with its technologies, tastes and needs, developed, or should have developed, its own and characteristic architecture. At the same time, architecture began to be seen as a structural organism, in which the structure was not just a simple necessity, but an intrinsic component of its conception.

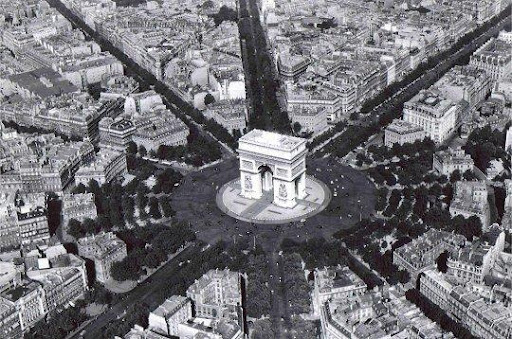

The last four decades of the 19th century witnessed the growth of cities and the scale of construction projects. Paris itself was the scene of this trend, with Haussmann's urban remodeling. The grandiose profile of the winning projects of the Grand Prix then matched the constructive demands of the new society. Urbanism became the main challenge of architecture and the École des Beaux-Arts began to teach notions of the subject, even without extensive knowledge of it.

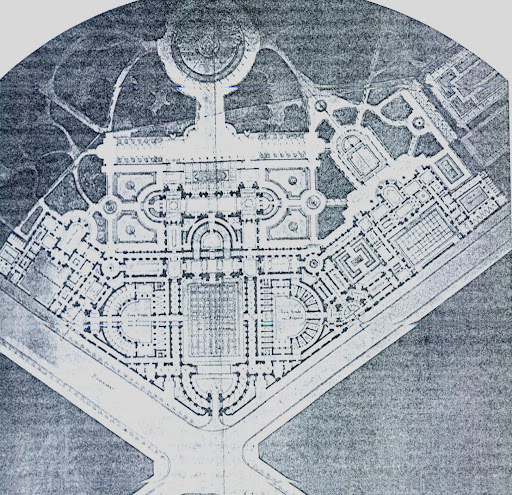

During the 1850s there were unsuccessful efforts to modify the Beaux-Arts system, in which the name of Félix Duban stands out. But it was in the 1860s that something really happened. École professors still taught in the same way, but some students picked up ideas from a single place: Charles Garnier's studio, then dedicated to the design of the Paris Opera, one of the most important monuments of the 19th century. This project, which lasted from 1862 to 1875, required exhaustive work and a large number of drawings. Its influence on the architect's collaborators was inevitable, who even used many of the architectural motifs in their designs competing for the Grand Prix (figure 3).

The Paris Opera was a widely commented work, which raised praise and criticism, in a great controversy. Its architectural characteristics, the volumetric composition in which the exterior masses should show the interior spaces (one of Charles Garnier's main principles), the decoration derived purely from the artist's inspiration and particular taste, the analogy between architecture and the human body, mark a new moment in French architecture and at the École: Eclecticism. From then on, comparisons between biological forms and architectural forms became part of the Beaux-Arts system.

- DREXLER Arthur (org). The Architecture of the École des Beaux-Arts. Londres: Secker & Warburg, 1984.

Eclecticism

Eclecticism, as it was called by its own contemporaries, was the characteristic architectural style of the second half of the 19th century and also the best known of that century. It was the culmination, in architecture, of the romantic culture, the industrial revolution, scientific development and the sharp expansion of urban centers.

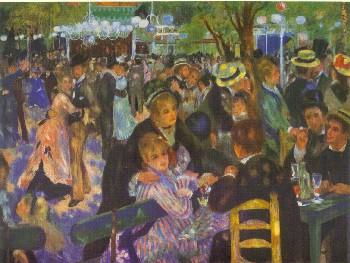

Eclectic architecture is a reflection of the era in which it flourished. Nineteenth-century society (Figure 4), dazzled by technological advancement (Figure 5) and economic development, unprecedented in human history, and feeling that it was in a totally superior era, yearned to freeze this reality and become definitive. But, at the same time, that same society knew that history is dynamic, constituting a constant evolution, and that the economy itself and technological advances must also be; for this reason it also longed for transformation and progress, for the very perpetuation of capitalism. Thus, there is an opposition between two opposing postures, which permeates all architectural practice: staticity and dynamism.

This opposition manifests itself in architecture through the simultaneous employment of dynamic and static form:

“[...] ECLETISM aims to create a dynamic form capable of incorporating the intense flows and technical progress of the industrial age. Inspired by this incessant movement, the dynamic form must allow the creation of a fluid and continuous internal space, which gradually dematerializes the architecture.” (PUPPI, 2006).

“[...] ECLETISM must represent the static image that society has of itself. The composition must also be the materialization of a static form: a centralized, hierarchical and closed order, capable of containing the process of internal dematerialization of architecture from the outside. If the future is unknown, and if the present is dynamic, the only source of static form is the forms and styles of architectural tradition themselves.” (PUPPI, 2006).

In other words, eclectic architecture is fluid and dynamic on the inside (figure 6) and closed and static on the outside (figure 7). The forms must also exactly represent the opposition between two contrary conceptions. This was achieved mainly through stylistic composition with the characteristic elements of past periods: more rationalist periods, more romantic periods, more austere periods, more allegorical periods were combined in the same building (probably deriving the name of the style from there) to establish totally perceptible contradictions (figure 8). But all these contradictions were intended to suggest a virtual unity, and more theoretically, a new architecture and a new social order.

For the rediscovery of all the architectures of the past, meticulous studies of monuments and research of stylistic elements were undertaken; not only from Europe itself, but even from eastern civilizations such as Arabia, India and China. This architectural “archaeology” was accompanied by the development of new techniques that allowed the imitation of different types of textures and materials, such as building stones, marble and wood (figure 9).

The theoretical discussion of architecture at the time was fervent. Authors defended specific styles of the past, proposing great revivals; others argued that the 19th century should find its own style, as all previous eras did. But, in any case, all these theorists “did not realize that they were heading in an anachronistic direction and did not see that the 19th century had already found ‘its own style’ and that this was Eclecticism.” (PATETTA, 1987, p. 13).

During the eclectic period, a new design method emerged, which also became characteristic, the synthetic-analytical method:

“The method is synthetic because the composition process moves from the whole to the parts: the opposition of opposites is a theoretical-methodological principle from which all parts derive and are generated. The method is analytical because the theoretical principle of opposition does not and cannot intend to achieve the unity of the parts: the contrary forms or forces must contradict each other visibly to reveal the absence of unity in architecture as in society.” (PUPPI, 2006).

Eclecticism also witnessed the emergence and use of new building materials, mainly iron, which gave rise to new architectural forms. Iron, in addition to building large bridges, machines and various utensils, was also incorporated into architecture, as a structural system, a wide variety of urban furniture, and even as ornaments. Noteworthy are the buildings made entirely of iron and glass, such as the pavilions for the universal exhibitions in London (figure 10) and Paris (figure 11). At the same time, engineering was emerging, with the development of material studies and precise calculations that allowed for an increasingly scientific treatment of construction.

All this architectural production and technological advances were driven by the triumphant bourgeoisie, a social class that emerged as dominant through the decline of the nobility and the consolidation of industrialization:

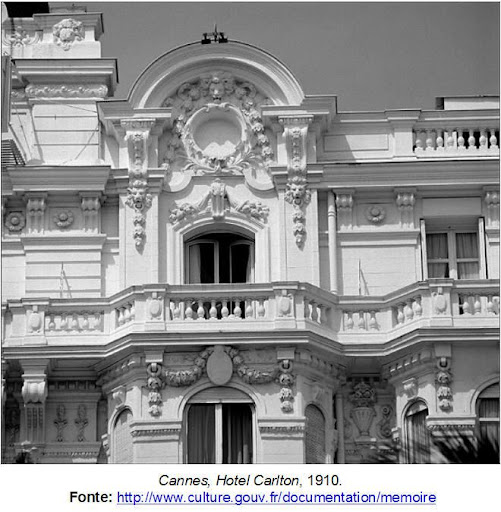

“[...] Eclecticism was the architectural culture of a bourgeois class that gave priority to comfort, loved progress (especially when it improved their living conditions), loved novelties, but demoted artistic and architectural production to the level of fashion and taste. It was the bourgeois clientele that demanded (and obtained) the great advances in technical installations, in the sanitary services of the house, in its internal distribution, that requested a rapid evolution of the typologies in the big hotels, in the spas, in the big stores, in the offices, in the stock exchanges, in theaters and in banks [...].” (PATETTA, 1987, p. 13).

Also according to PATETTA (1987), Eclecticism can be divided into three main currents: that of stylistic composition, which represented the faithful and coherent imitation of past styles (figure 12); that of typological historicism, which presented an analogical relationship between the use of buildings and the style to be adopted (figure 13); and that of compositional pastiches, which represented the free possibility of choosing styles to compose completely new solutions (figure 14).

Eclecticism was not just an architectural style, it also extended to urban planning. The city in the second half of the 19th century had to deal with growth in unprecedented scales of urban factors, such as the road system, vehicle fleet, population and services; everything interconnected and constituting a dematerialized space basically composed of flows. In this context, only architecture has the power to materialize some static spatial order. The urban tissue starts to be composed by blocks of continuous constructions, in line with the sidewalk, with trivial lists of spaces, interspersed by isolated constructions showing all their facades, richly decorated and with special lists of spaces, the monuments (figure 15). Large tree-lined avenues were opened for pedestrians and road traffic, public parks and neighborhoods destined for different activities, including the new and luxurious residences of the ruling bourgeoisie. This entire new urban layout is inspired by the urban criteria of the Baroque period, such as the axes of symmetry, the geometrization of space and straight streets that open up perspectives for monuments.

Just like architecture, the eclectic city also represents an opposition of two contrary conceptions, a dynamic space and a static space:

“The immaterial, decentralized and fluid space-network constitutes the dynamic pole of this spatial opposition. At the other extreme, the hierarchical order formed by the set of closed, centralized and massive architectural volumes represents the static pole of the eclectic city.” (PUPPI, 2006).

The organization of all these urban elements takes place according to a strict order that brings the city closer to the notion of “organism”, also present to some extent in architecture, and which requires that each element play a role in the whole:

“Whether in the years of the [French] Empire (1805 – 1815), or in those of the [European] capital cities (1850-80), urbanism established a precise hierarchy of urban structures (which coincided, of course, with the economic and class hierarchy social). [..].” (PATETTA, 1987, p. 23).

Typically, this hierarchy dictated that the more important the building, the more elaborate it should be. It is of course the monuments. In a more generic classification, it could be said that the order of importance started from cult monuments, such as cathedrals (religious power), passing through monuments of self-celebration of the bourgeoisie, such as opera houses (economic power), and culminating in in the monuments of the administration, such as the imperial palaces (political power), the most important. This importance was conferred on a monument by a notion called architectural “character”, which also gave recognition to its function:

“Character is attributed to a building by revealing and demonstrating the cultural, historical and social particularities of the list of spaces. The exposure of the particular quality of the building gives it its own character that differentiates it from the others. The architectural character gives life to the monument: it communicates to the public the social and cultural value of each monument, as well as its place in the urban hierarchy that architecture itself must organize, materialize and represent.” (PUPPI, 2006).

Eclecticism adapted very well to the period of emergence of the modern society of consumption and mass information, in which the rising bourgeoisie asserted itself and extended the possibility of choice and customization to architecture. It reached the beginning of the 20th century, already exhausted and stripped of its most important principles through the practice of the compositional “anything goes”. Then came a new reaction, which turned radically against some aspects of this decadent architecture, such as ornamental excess, the imitation of materials, the accentuated concern with form to the detriment of function, and the concealment of all recent construction technologies. It was the Modern Movement, which made a complete break with architectural tradition, in the formal sense, by abandoning any and all decorative elements. But contrary to what is commonly thought, Eclecticism was never completely abandoned:

“Despite fighting eclecticism, MODERN ARCHITECTURE revitalizes the eclectic method of composition. The 20th-century avant-garde replaced historical styles with abstract art to maximize the eclectic opposition of opposites. Leveraging the opposition between dynamic and static form, MODERN ARCHITECTURE synthesizes, materializes and symbolizes the machine age. It replaces eclecticism in order to better realize its own objective: to be the definitive and contradictory style of an increasingly dynamic and contradictory society.” (PUPPI, 2006).

This architecture arrived in Brazil in the last quarter of the 19th century, considered as a symbol of modernity and civility. The country was still predominantly agrarian and culturally backward in relation to Europe. The existing bourgeoisie was made up mainly of coffee farmers, the main export product that structured the economy. Eclecticism in Brazil was closely linked to the economic empire of coffee, which also sponsored the modernization of construction techniques at the same time.

When Brazil began to experience the outbreaks of industrialization and urbanization, already consolidated in Europe for a long time, the architecture in fashion was still Eclecticism. For this reason, most Brazilian cities have established themselves aesthetically linked to eclectic culture. This consolidation took place through constructions, from public and institutional buildings to residences, and through the urban structures themselves. It was the richest architectural period in the entire history of the country, which extended from north to south and still remains in the oldest centers of some cities.

Brazil has not gone through most architectural periods in western history; practically the only good architecture that developed in the country was Eclecticism, precisely the last good architecture in that history.

- PATTETA, Luciano. Considerações sobre o Ecletismo na Europa. In: FABRIS, Annateresa. Ecletismo na Arquitetura Brasileira. São Paulo: Nobel Edusp, 1987.

- PUPPI, Marcelo. Notas de aula, 2006.

- http://www.arscientia.com.br/materia/ver_materia.php?id_materia=242, consulted on 08/15/09, at 20:10h.

- http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:La_Madeleine_de_Par%C3%ADs.JPG, consulted on 08/16/09 at 18:30h.

- http://www.dezenovevinte.net/arte%20decorativa/hotel_balneario.htm, consulted on 08/16/09 at 18:00h.

- http://docshistoria11-cr-esmaia.blogspot.com/2008/05/o-desenvolvimento-da-indstria.html, consulted on 08/16/09 at 17:30h.

- http://flickr.com/photos/gifted_ce/2265670350/, consulted on 08/16/09 at 17:50h.

- http://nautilus.fis.uc.pt/cec/designintro/industrial.html, consulted on 08/16/09 at 18:20h.

- parisseculoxix.blogspot.com/, consulted on 08/16/09 at 18:20h.

- http://ruyi-book-travel.blogspot.com/2007/10/who-made-paris-like-that.html, consulted on 08/16/09 at 18:50h.

- http://www.skyscrapercity.com/showthread.php?t=709166&page=2, consulted on 08/16/09 at 17:45h.

- http://www.vivercidades.org.br/publique_222/web/cgi/cgilua.exe/sys/start.htm?infoid=1105&sid=21&tpl=printerview, consulted on 07/24/09 at 15:10h.

Ornament And Architecture

The need for ornament in architecture is indisputable. However, from the beginning of the 20th century to the present time, architectural production has completely abandoned architectural decoration and is increasingly moving away from it.

The so-called Modern Movement, which overthrew decadent eclectic architecture, was a response to the profound social transformations underway since the end of the 19th century and intended to represent the new society. This new attitude towards architecture emerged amid the exaltation of industrialization and the machine, and imbued with a utopia of a better future. It was the celebration of the “new era”, which, in order to be better, had to break with the past. Similar postures appeared in virtually all other arts and the predominant aesthetic in the artistic world became formal abstraction.

In this war against the past, permeated by the growing fascination with the novelties of modern life, the forces turned, among others, against a characteristic common to all previous eras: ornamentation. Inspired by the decorative excesses of late Eclecticism and by the speed of displacement and information flows, authors from all over the world proposed ideas, often absurd and fallacious, about the need to abandon decorativism in architecture. Adolf Loos published in 1908 the famous article “Ornament and Crime”, in which he even used arguments of a moral nature to justify the contempt for ornamentation. Le Corbusier, considered one of the masters of the Modern Movement in architecture, published in 1923 the famous book “For an Architecture”, in which he defended that architecture should approach the notion of “machine”, due to its total functionality, from which its beauty origins should derive. And many others have also propounded diverse similar arguments with the same object.

The theory of modern architecture at the beginning clearly had a messianic character, in which only new conceptions could “save” humanity in terms of culture and point to a better future. In this context, the ornament was considered the villain, concentrating all the evils of the culture of the past. Words like “progress”, “evolution”, “superiority”, and similar ones were frequently used by defenders of modernism in relation to the criticism against architectural ornamentation. There was even a manipulation of theorists' ideas, in which only the convenient parts were used, to serve the modernist discourse. The North American architect Louis Sullivan, for example, was not totally against ornamentation, but a phrase from one of his works, “form follows function”, was widely disseminated, displaced from its purpose and implying a radicalism that was foreign to his ideas.

But two and a half thousand years of architecture, ranging from classical Greco-Roman antiquity to the Eclecticism of the early 20th century, in which ornament was an essential part, cannot have been wrong and architecture cannot have simply been “corrected” by modernity. What the Modern Movement forgot, in this attempt at a radical rupture with the past, is that the ornament associated with the architectural composition constitutes the manifestation of an archetype (SÀ, 2005, p. 25). Archetypes are “[...] psychic images of the collective unconscious that are the common heritage of all humanity.” (FERREIRA apud SÁ, 2005, p. 23). For this reason, throughout history, humanity has had a natural tendency to decorate everything necessary for life, from everyday objects to buildings.

It is precisely the ornament that gives crude and coarse elements, in the case of architecture, structural and sealing systems, identity with nature and with human spirituality. This identity is architecture's ability to communicate, establishing a moral and intellectual dimension. The notion of nature must be emphasized, as it is to it that the human being belongs, and not to the machine and mechanical universe, as the Modern Movement wanted to suppose. Thus, ornament is an essential part of architecture, so that there can be no good architecture without ornamentation.

Throughout the architectural tradition of two and a half millennia, the ornaments and decorative rules of architecture had educational and moralistic functions. But from the 19th century onwards, with the development of new communication systems, such as photography, radio, and cinema, and the consequent formation of mass information transmission, architecture lost its role as an image propagator. But that does not justify its stripping of ornamentation, as the modernists wanted. While the “spirit of the modern age” contemplates speed, mechanization, and massification, which are values totally foreign to the human condition and therefore must be moderated, architecture still has any and all natural values to communicate and thus contribute to a better future. And it is the ornamentation that will make this communication. For any time and place, the wise statement by the English theorist John Ruskin is valid that ornaments are “[...] the defining elements of architecture as art”. (PAIM apud SÁ, 2005, p. 91).

- SÁ, Marcos Moraes de. Ornamento e Modernismo: A Construção de Imagens na Arquitetura. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 2005.

The Classic Design Method And Functionality

During the entire period in which the classical rules of architecture prevailed, configuring the so-called architectural tradition, some volumetric and stylistic composition techniques were also applied to the design process of the building. Mainly symmetry, formal rigor and clarity. This resulted in regular plans, closed in on themselves and originating orderly and legible spaces. The Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris brought this method to its peak; the so-called Beaux-Arts method was based on all these characteristics.

The projects developed in this way presented a volumetric balance and perfect symmetry between each part of the set, with a symmetrical correspondence between the openings, doors, windows or niches, both vertically and horizontally. Users, once inside these buildings, were able to perfectly apprehend the space and, moreover, this space welcomed them, due to its perfect configuration.

There was also a symmetrical, or at least orderly, correspondence between the functional spaces themselves. They were each intended for a function without overlapping, and were arranged harmoniously along a central circulation hall or corridors. All this greatly facilitated the development of the activities that the project was supposed to house, in addition to making the circulation of users practical and fluid.

The Modern Movement exalted functionality as the starting point of all architecture, but paradoxically broke with the classic design method and did not propose any other with the same efficiency. That is still the best method for functionality development and also for user comfort. The layout of the plan, the internal treatment of the building and its interior and exterior ornamentation must form a unit.

This unit, along with the design potentialities described, is what should provide pleasure to the user. As Marcia David said:

“[...] what brings pleasure in architecture is not just the external beauty of the building, its sculptural condition, its decorative elements, but what the set provides when experiencing it. Architecture is to be lived. [...] Individuals have expectations of the places they use, and among them, that of establishing emotional bonds that allow them to identify themselves as part of these places. The place, when perceived, gives the viewer, in addition to its purpose, the subjective qualities consistent with that purpose. It is at stake for the user, its adequacy, compromising and qualifying its reception, its involvement and its conception of place, which is unique and subjective.” (www.arquitextos.com.br/arquitextos/arq000/esp347.asp).

- www.arquitextos.com.br/arquitextos/arq000/esp347.asp, consulted on 08/04/09 at 15:30h.